Empirical Methods in Finance

Practicing 1

Basic Statistics

Basic stats

The following are simple examples of how to compute basic statistics using R. We will start importing the data. Let’s use the free dataset iris, available in R.

First, explore the dataset.

'data.frame': 150 obs. of 5 variables:

$ Sepal.Length: num 5.1 4.9 4.7 4.6 5 5.4 4.6 5 4.4 4.9 ...

$ Sepal.Width : num 3.5 3 3.2 3.1 3.6 3.9 3.4 3.4 2.9 3.1 ...

$ Petal.Length: num 1.4 1.4 1.3 1.5 1.4 1.7 1.4 1.5 1.4 1.5 ...

$ Petal.Width : num 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.2 0.1 ...

$ Species : Factor w/ 3 levels "setosa","versicolor",..: 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ...- We have 5 variables: Sepal.Length, Sepal.Width, Petal.Length, Petal.Width e Species. The first four are numeric while the last is a string with three groups: setosa, versicolor, and virginica. The dataset contains 150 observations

Basic stats

Let’s take a look at the first 10 observations in the dataset.

Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width Species

1 5.1 3.5 1.4 0.2 setosa

2 4.9 3.0 1.4 0.2 setosa

3 4.7 3.2 1.3 0.2 setosa

4 4.6 3.1 1.5 0.2 setosa

5 5.0 3.6 1.4 0.2 setosa

6 5.4 3.9 1.7 0.4 setosa

7 4.6 3.4 1.4 0.3 setosa

8 5.0 3.4 1.5 0.2 setosa

9 4.4 2.9 1.4 0.2 setosa

10 4.9 3.1 1.5 0.1 setosaBasic stats

Now, let’s take a look at the first 5 observations of each species.

Species: setosa

Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width Species

1 5.1 3.5 1.4 0.2 setosa

2 4.9 3.0 1.4 0.2 setosa

3 4.7 3.2 1.3 0.2 setosa

4 4.6 3.1 1.5 0.2 setosa

5 5.0 3.6 1.4 0.2 setosa

------------------------------------------------------------

Species: versicolor

Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width Species

51 7.0 3.2 4.7 1.4 versicolor

52 6.4 3.2 4.5 1.5 versicolor

53 6.9 3.1 4.9 1.5 versicolor

54 5.5 2.3 4.0 1.3 versicolor

55 6.5 2.8 4.6 1.5 versicolor

------------------------------------------------------------

Species: virginica

Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width Species

101 6.3 3.3 6.0 2.5 virginica

102 5.8 2.7 5.1 1.9 virginica

103 7.1 3.0 5.9 2.1 virginica

104 6.3 2.9 5.6 1.8 virginica

105 6.5 3.0 5.8 2.2 virginicaMean and Median

Now, let’s find the means and the medians of the four numeric variables. The most intuitive way is as follows.

Mean and Median

But this is the easiest way.

Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width

Min. :4.300 Min. :2.000 Min. :1.000 Min. :0.100

1st Qu.:5.100 1st Qu.:2.800 1st Qu.:1.600 1st Qu.:0.300

Median :5.800 Median :3.000 Median :4.350 Median :1.300

Mean :5.843 Mean :3.057 Mean :3.758 Mean :1.199

3rd Qu.:6.400 3rd Qu.:3.300 3rd Qu.:5.100 3rd Qu.:1.800

Max. :7.900 Max. :4.400 Max. :6.900 Max. :2.500

Species

setosa :50

versicolor:50

virginica :50

Mean and Median

See that in the code above you also have the number of observations of each species. If you wanted to know how many observations you have in the dataset, you could use the following line. This might be important in the future.

Mean and Median

If you want the same thing by group, do as follows:

iris$Species: setosa

Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width

Min. :4.300 Min. :2.300 Min. :1.000 Min. :0.100

1st Qu.:4.800 1st Qu.:3.200 1st Qu.:1.400 1st Qu.:0.200

Median :5.000 Median :3.400 Median :1.500 Median :0.200

Mean :5.006 Mean :3.428 Mean :1.462 Mean :0.246

3rd Qu.:5.200 3rd Qu.:3.675 3rd Qu.:1.575 3rd Qu.:0.300

Max. :5.800 Max. :4.400 Max. :1.900 Max. :0.600

Species

setosa :50

versicolor: 0

virginica : 0

------------------------------------------------------------

iris$Species: versicolor

Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width Species

Min. :4.900 Min. :2.000 Min. :3.00 Min. :1.000 setosa : 0

1st Qu.:5.600 1st Qu.:2.525 1st Qu.:4.00 1st Qu.:1.200 versicolor:50

Median :5.900 Median :2.800 Median :4.35 Median :1.300 virginica : 0

Mean :5.936 Mean :2.770 Mean :4.26 Mean :1.326

3rd Qu.:6.300 3rd Qu.:3.000 3rd Qu.:4.60 3rd Qu.:1.500

Max. :7.000 Max. :3.400 Max. :5.10 Max. :1.800

------------------------------------------------------------

iris$Species: virginica

Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width

Min. :4.900 Min. :2.200 Min. :4.500 Min. :1.400

1st Qu.:6.225 1st Qu.:2.800 1st Qu.:5.100 1st Qu.:1.800

Median :6.500 Median :3.000 Median :5.550 Median :2.000

Mean :6.588 Mean :2.974 Mean :5.552 Mean :2.026

3rd Qu.:6.900 3rd Qu.:3.175 3rd Qu.:5.875 3rd Qu.:2.300

Max. :7.900 Max. :3.800 Max. :6.900 Max. :2.500

Species

setosa : 0

versicolor: 0

virginica :50

Minimum and maximum

The function summaryalready gives you the minimum and maximum of all variables. But sometimes you need to find only these values. You could use the following lines.

You could also find the range of values to find the extreme values of a variable.

Minimum and maximum

If you need the distance between the extreme values, you can use:

Standard-deviation and Variance

Finally, you can also compute the Standard-deviation and Variance of one variable as follows.

If you want the standard deviation of all variables:

Correlation

The following lines will show you a correlation table. First, you need to create a new dataframe with only the numeric variables. This is an extremely important table to your academic paper.

Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width

Sepal.Length 1.0000000 -0.1175698 0.8717538 0.8179411

Sepal.Width -0.1175698 1.0000000 -0.4284401 -0.3661259

Petal.Length 0.8717538 -0.4284401 1.0000000 0.9628654

Petal.Width 0.8179411 -0.3661259 0.9628654 1.0000000Frequence table

Here is another important table you might use in your paper: the frequency of observations by group.

T-test

Let’s create now a t-test of the difference in means. For that, we will use another dataset: mtcars. The data was extracted from the 1974 Motor Trend US magazine, and comprises fuel consumption and 10 aspects of automobile design and performance for 32 automobiles. You can find the description of the variables here.

You will find that there is one variable that is binary: either the cars are automatic (1) or are manual (0).

When you have binary variables, it is always a good idea to test if the means of the variables are different between the two groups of the binary variable.

This is a big thing and you will use a lot in your academic research. In fact, in many articles, the authors explore and compare two groups. So, be ready to create such an analysis.

T-test

First, import the new dataset. Then, repeat the first steps and inspect this dataset (I will not inspect the dataset here, but you should inspect as a way to practice it).

T-test

Then, use the binary variable to see if other variables have similar means. The following case compares the average of mpg (miles p/ gas) of automatic vs. manual car.

Welch Two Sample t-test

data: mpg by am

t = -3.7671, df = 18.332, p-value = 0.001374

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means between group 0 and group 1 is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-11.280194 -3.209684

sample estimates:

mean in group 0 mean in group 1

17.14737 24.39231 - We see that the average in the automatic car is around 17.1 while the average of manual cars is 24.3.

- These averages are statistically different, since the t-stat is high (-3.76).

- So, we can learn that automatic cars consume more gas than manual cars.

- This type of test will be very important in your research.

Dispersion

These measures show how spread out the data are around the mean.

The coefficient of variation (CV) compares variability relative to the mean — useful in finance for comparing volatility across assets.

Interquartile Range = \(Q_3 - Q_1\)

Quantiles & Percentiles

Quantiles divide the data into equal parts (e.g., quartiles, percentiles).

They are often used to identify thresholds or outliers.

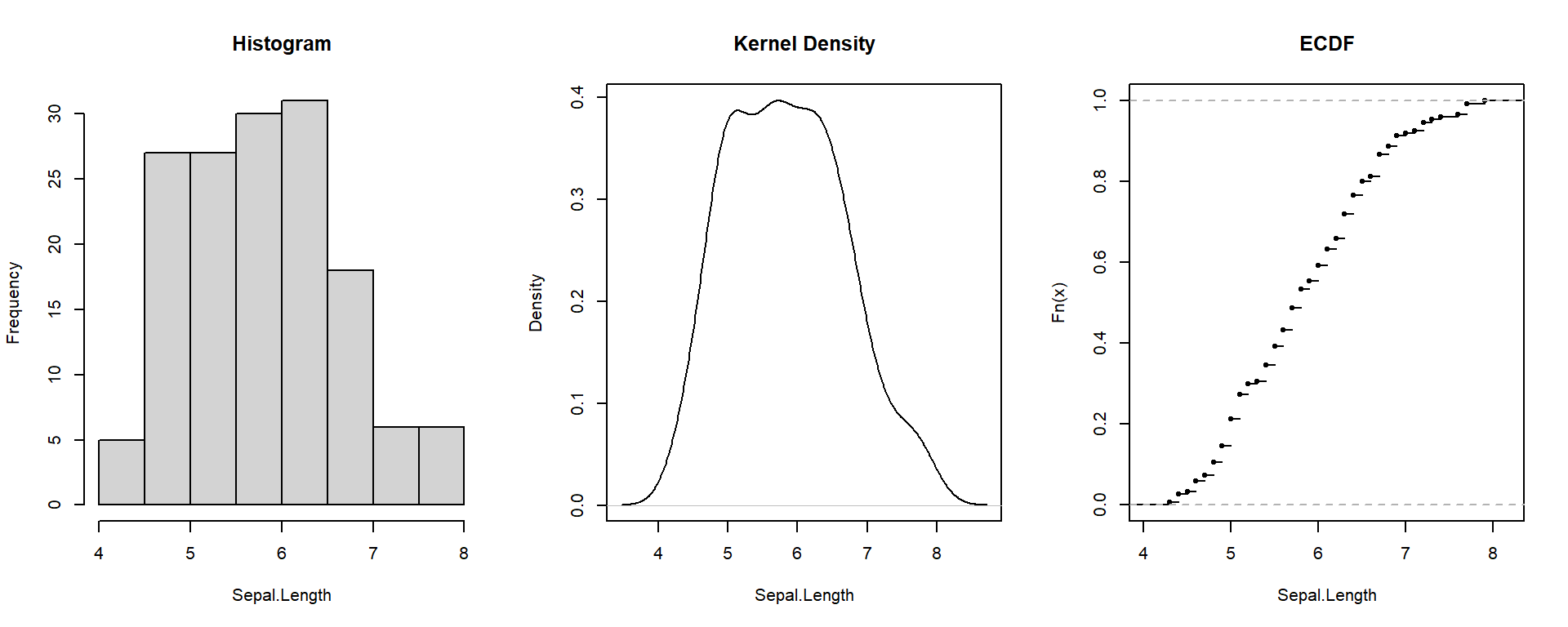

Distributions

Visualizing the distribution helps you see its shape — whether symmetric, skewed, or concentrated.

Empirical Cumulative Distribution Function (ECDF) = y-axis shows the accumulated proportion of observations below the x-value.

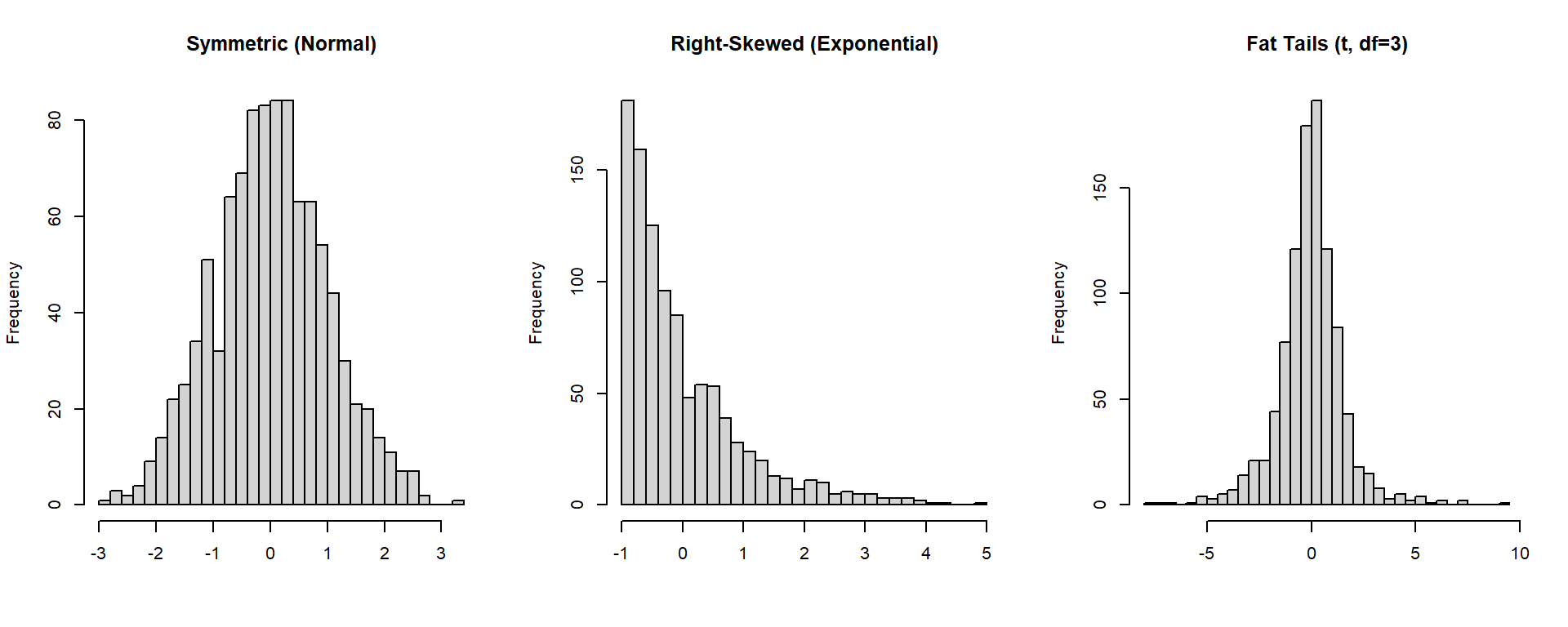

Shape: Skewness & Kurtosis

These measures describe the shape of a distribution.

- Skewness: measures symmetry (right- or left-tailed).

- Kurtosis: measures tail heaviness (fat tails → more extreme events).

set.seed(123)

x_sym <- rnorm(1000, mean = 0, sd = 1) # symmetric (normal)

x_right <- rexp(1000, rate = 1) - 1 # right-skewed

x_fat <- rt(1000, df = 3) # heavy tails (t-distribution)

par(mfrow = c(1,3))

hist(x_sym, breaks = 25, main = "Symmetric (Normal)", col = "lightgray", xlab = "")

hist(x_right, breaks = 25, main = "Right-Skewed (Exponential)", col = "lightgray", xlab = "")

hist(x_fat, breaks = 25, main = "Fat Tails (t, df=3)", col = "lightgray", xlab = "")

Shape: Skewness & Kurtosis

Now, let’s compute skewness and kurtosis for our actual data.

- Skewness > 0 → right tail longer (positive skew).

- Skewness < 0 → left tail longer (negative skew).

- Kurtosis > 0 → heavier tails than normal (leptokurtic).

- Kurtosis < 0 → lighter tails than normal (platykurtic).

Outliers via IQR Rule

Outliers are points far from most observations. The IQR rule defines them as values beyond 1.5 × IQR from the quartiles.

x <- iris$Sepal.Length

Q1 <- quantile(x, .25); Q3 <- quantile(x, .75); I <- IQR(x)

lower <- Q1 - 1.5*I; upper <- Q3 + 1.5*I

out_idx <- which(x < lower | x > upper)

list(

thresholds = c(lower = lower, upper = upper),

n_outliers = length(out_idx),

example_values = head(x[out_idx], 5)

)$thresholds

lower.25% upper.75%

3.15 8.35

$n_outliers

[1] 0

$example_values

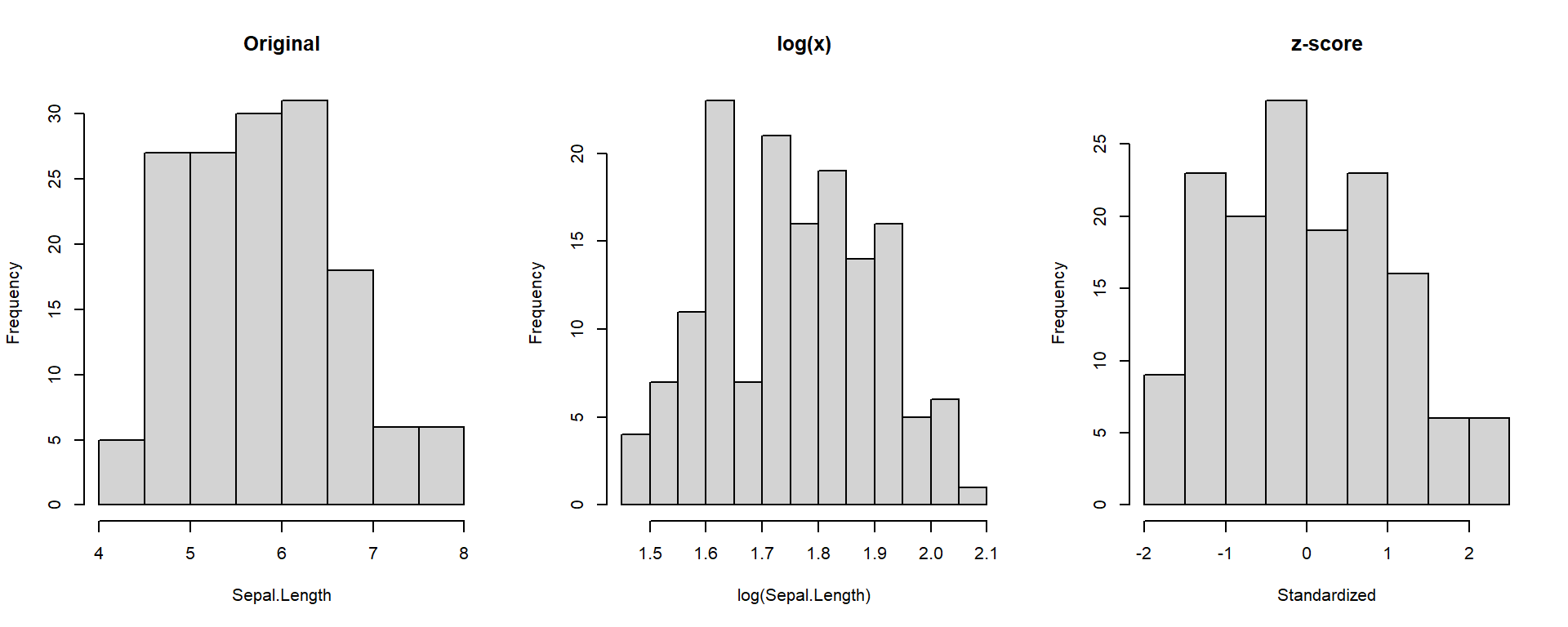

numeric(0)Transformations: log & z-score

Transformations help stabilize variance and make variables comparable.

- log(x) reduces skewness.

- z-score standardizes scale.

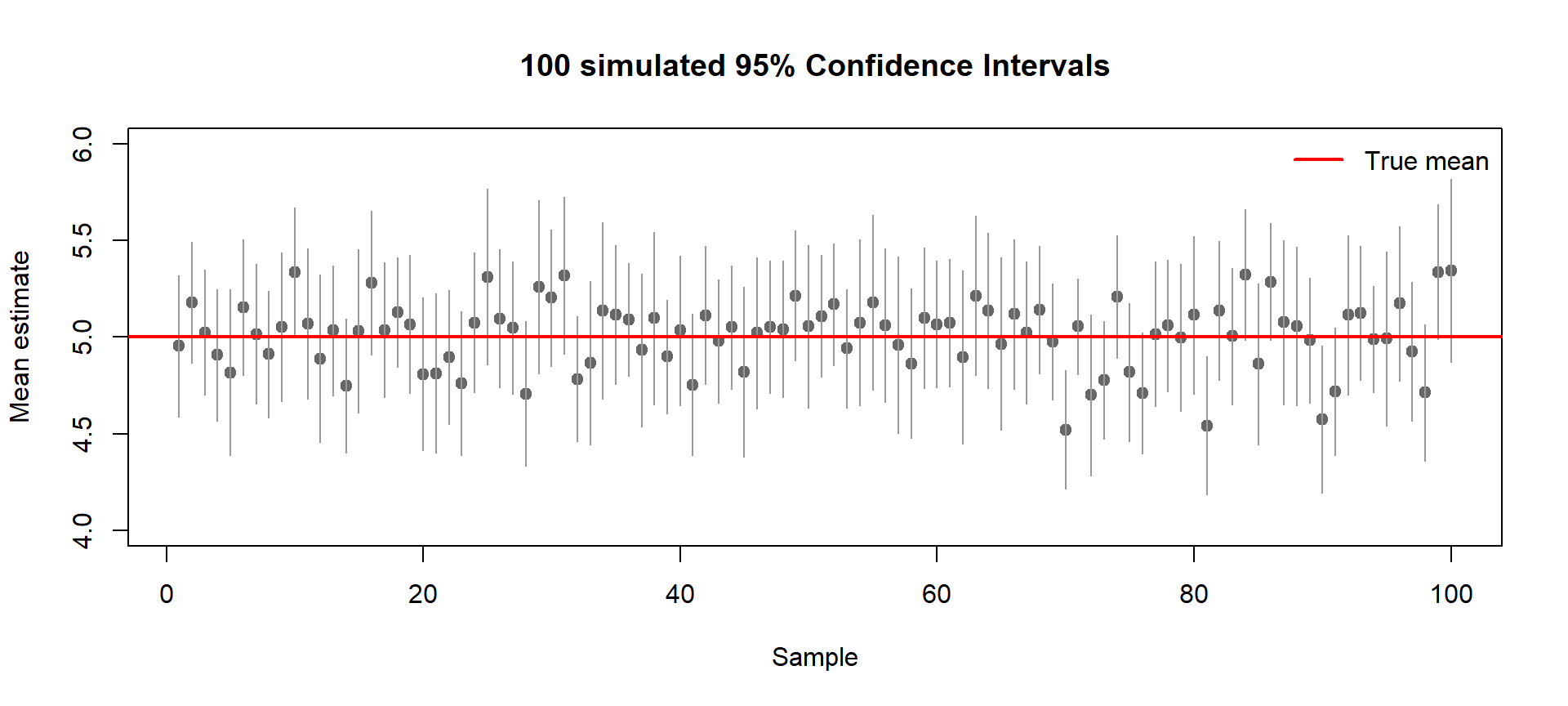

Confidence Intervals

What is a Confidence Interval?

A confidence interval reflects the uncertainty around an estimate.

If we repeat the experiment many times, most intervals will capture the true mean, but some will miss it just by chance.

Below, we simulate 100 random samples (each with 30 observations from a true mean of 5).

Each horizontal line shows a 95% confidence interval for one sample mean.

The red line marks the true mean (μ = 5).

- Gray dots: sample means

- Gray bars: confidence intervals

- Intervals that miss the red line show random sampling error

- About 5 out of 100 intervals are expected to miss (≈5%)

👉 A 95% CI means: if we repeated the experiment many times, 95% of the intervals would contain the true mean.

Visual Intuition

set.seed(123)

n <- 30

Nrep <- 100

mu <- 5; sigma <- 1

samples <- replicate(Nrep, rnorm(n, mu, sigma))

means <- colMeans(samples)

ses <- apply(samples, 2, sd) / sqrt(n)

lower <- means - qt(0.975, df = n-1) * ses

upper <- means + qt(0.975, df = n-1) * ses

plot(1:Nrep, means, ylim = c(4,6), pch = 19, col = "gray40",

ylab = "Mean estimate", xlab = "Sample",

main = "100 simulated 95% Confidence Intervals")

segments(1:Nrep, lower, 1:Nrep, upper, col = "gray60")

abline(h = mu, col = "red", lwd = 2)

legend("topright", legend="True mean", col="red", lwd=2, bty="n")

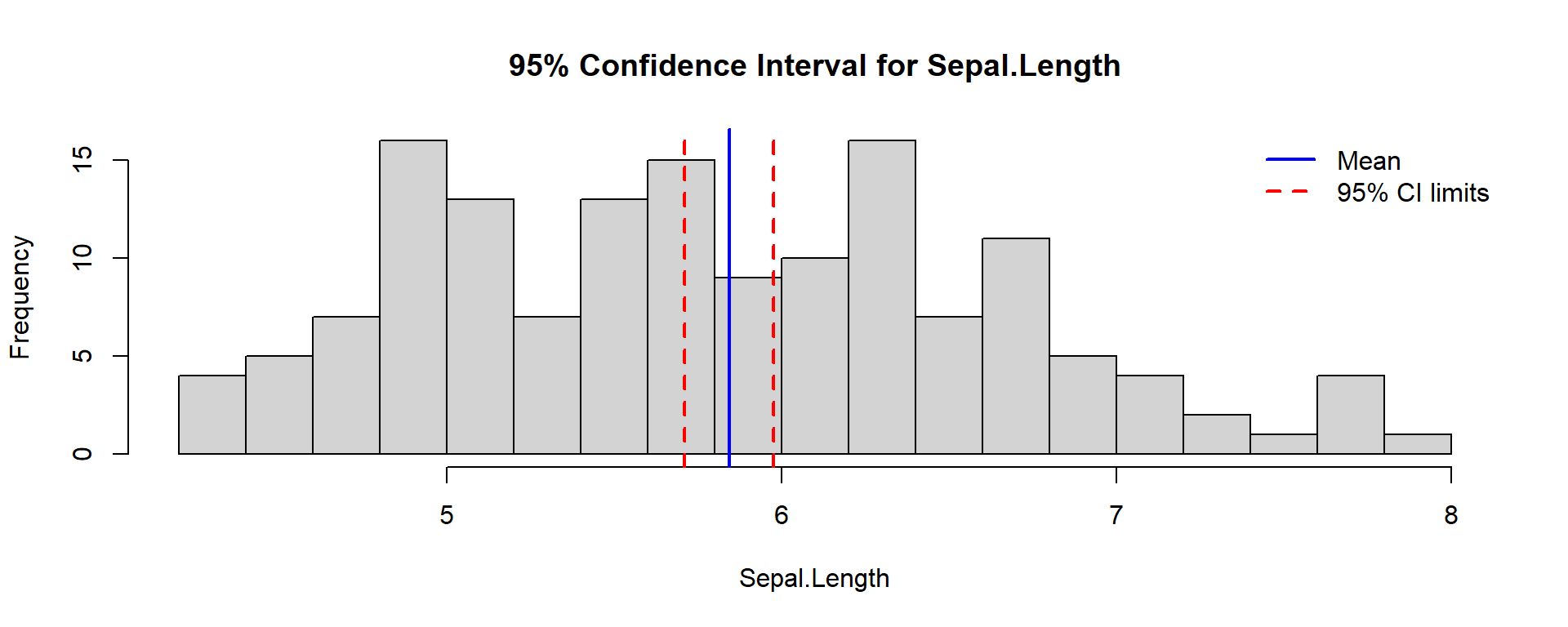

Confidence Interval for Iris Data

Compute a real example for Sepal.Length.

One Sample t-test

data: iris$Sepal.Length

t = 86.425, df = 149, p-value < 2.2e-16

alternative hypothesis: true mean is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

5.709732 5.976934

sample estimates:

mean of x

5.843333 👉 The output shows:

- Sample mean

- Confidence limits

- t-statistic and p-value

You can visualize the result below.

x <- iris$Sepal.Length

m <- mean(x)

se <- sd(x)/sqrt(length(x))

ci <- m + c(-1,1)*qt(0.975, df=length(x)-1)*se

hist(x, breaks = 15, col = "lightgray",

main = "95% Confidence Interval for Sepal.Length",

xlab = "Sepal.Length")

abline(v = m, col = "blue", lwd = 2)

abline(v = ci, col = "red", lty = 2, lwd = 2)

legend("topright", legend=c("Mean", "95% CI limits"),

col=c("blue","red"), lwd=2, lty=c(1,2), bty="n")

🙋️ Any Questions?

Thank You!

Henrique C. Martins [henrique.martins@fgv.br][Do not use without permission]