Main Results (Model 1)

2021-04-05

Over the last few years, there is a massive interest in corporate ESG decisions (disclosure and performance) from academia and practitioners.

To invest more in ESG practices, corporations are facing pressure from:

However, antecedents and consequences of ESG practices are not well defined in the literature.

The literature has two main hypotheses to explain why managers invest in ESG practices

1) The altruist/agency conflict argument

It says that ESG practices are value-decreasing decisions and, thus, a form of agency conflict.

The main reason managers invest in such practices is altruism.

2) The strategic argument

It says that ESG practices are value-increasing decisions and, thus, a way to differentiate from competitors. “Escape from competition” effect.

The main reason managers invest in such practices is to find value in ‘non-traditional’ ways.

Literature shows conflicting evidences: Barnea and Rubin (2010), Borghesi et al. (2014); Fernández-Kranz and Santaló (2010), Flammer (2015a), and Vural-Yavaç (2020).

The ‘Escape from competition argument’ is less likely to hold, because:

Worse Investor protection, higher agency problems

Poor institutions, high corruption

Corporate practices are more opaque

Thus, stakeholders are less likely to evaluate correctly the returns of strategies based on ESG practices, even profitable ones.

Hypothesis 1: Competition is negatively associated with corporate ESG practices.

Hypothesis 2: An increase in competition decreases corporate investment in ESG practices.

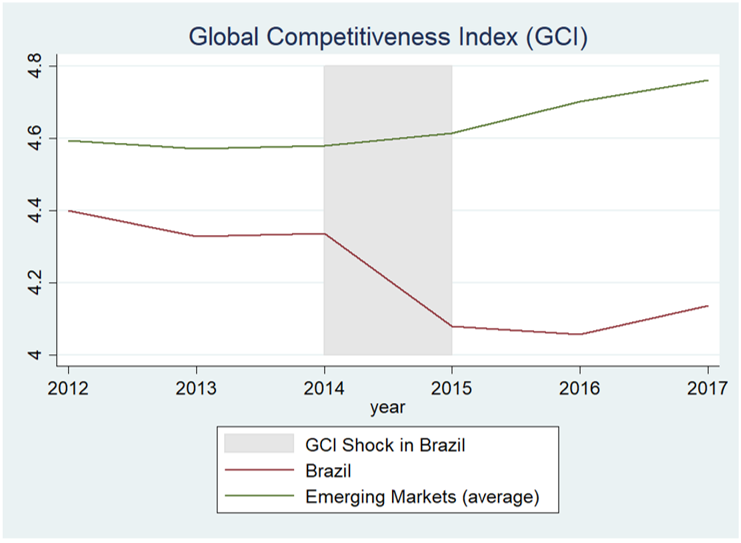

Beginning of a presidential impeachment

Negative GDP growth of about 3.5%

Skyrocketing inflation of about 10.5%

Decrease in exports and imports of goods and services of around 14% and 24%, respectively.

Source: World Economic Forum.

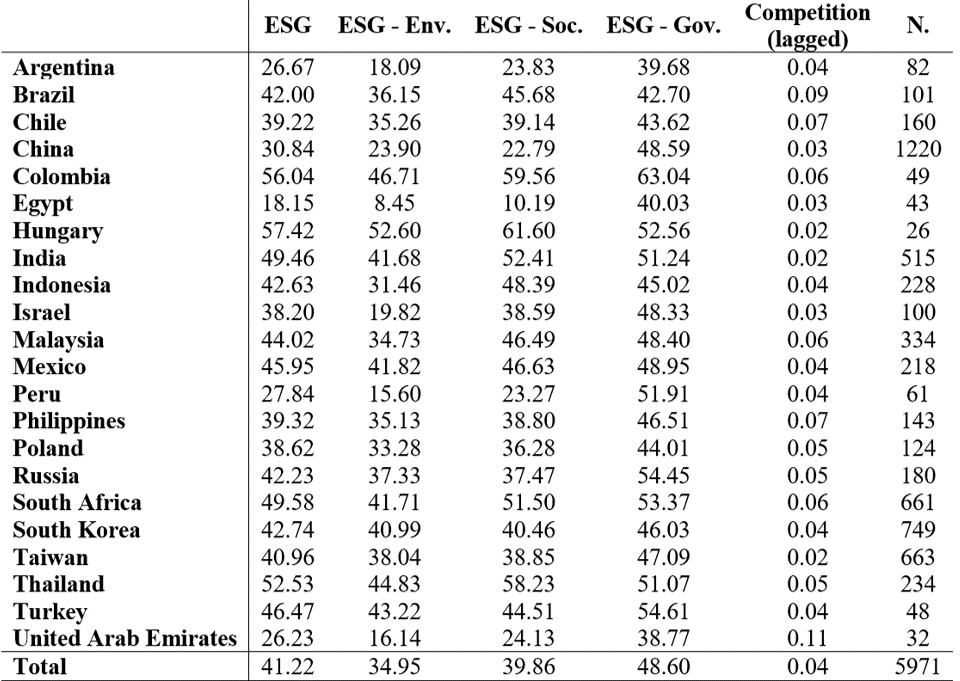

Sample of 5.971 firm-year observations for 22 emerging economies (Kearney, 2012)

Period: 2011-2019

Database: Thomson Reuters Eikon

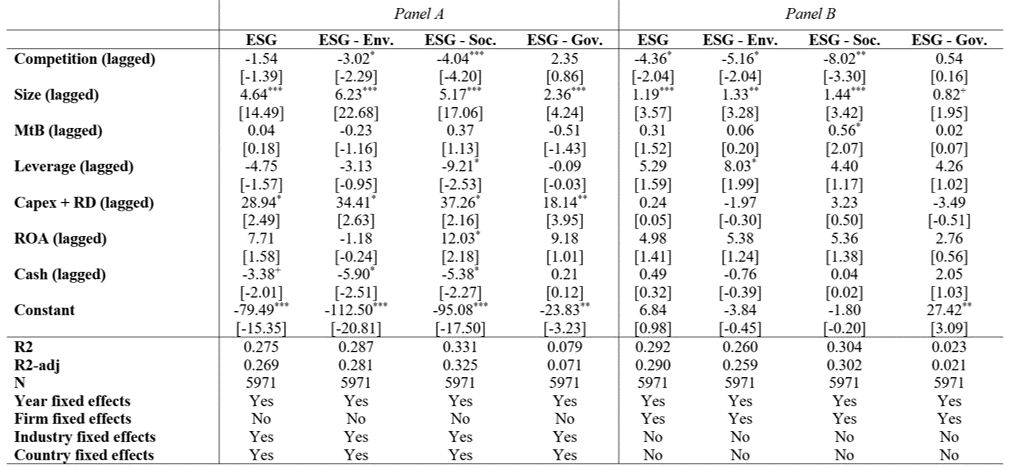

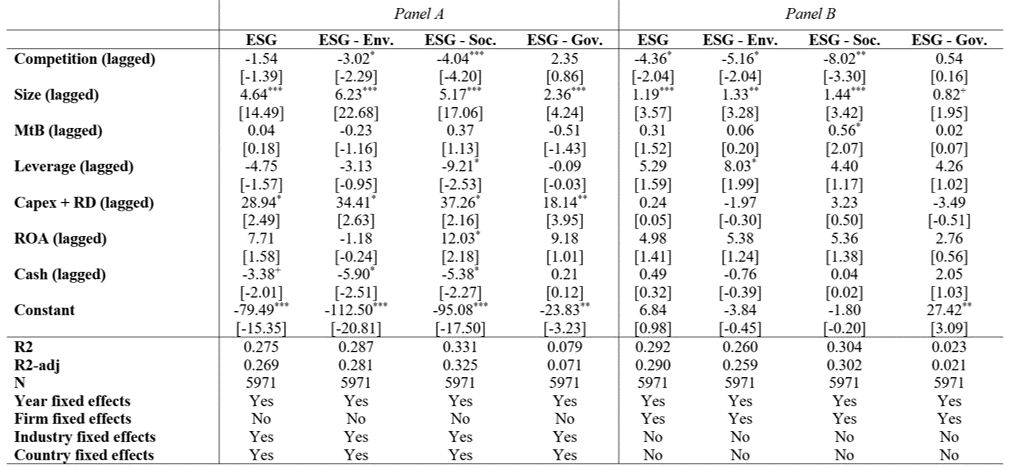

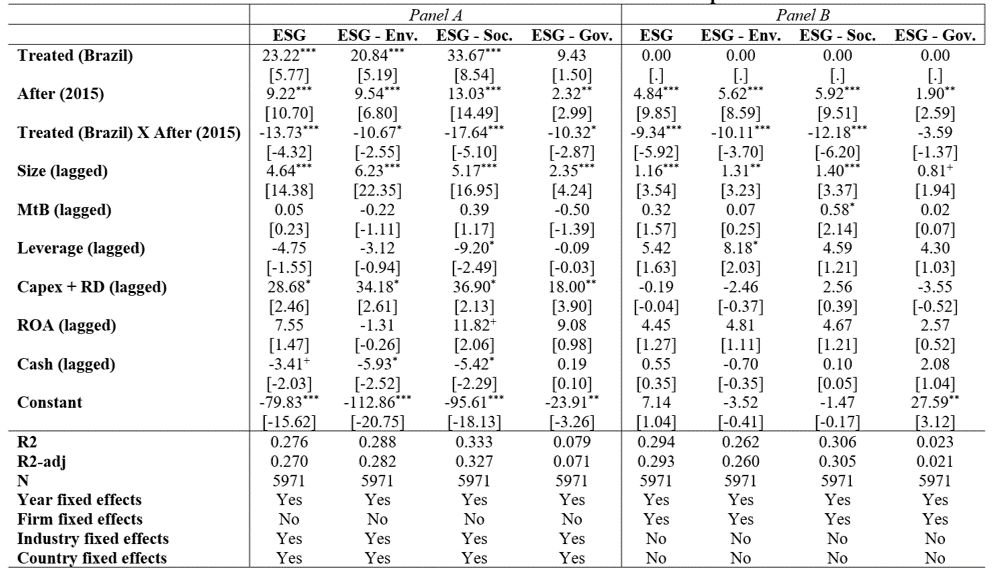

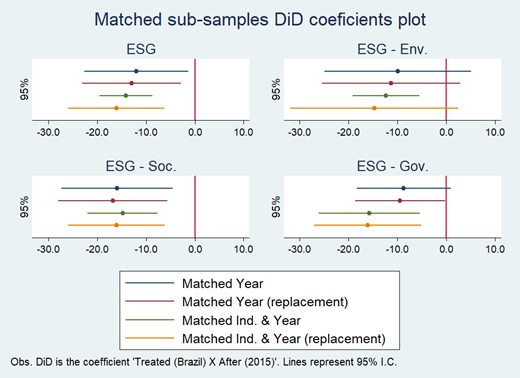

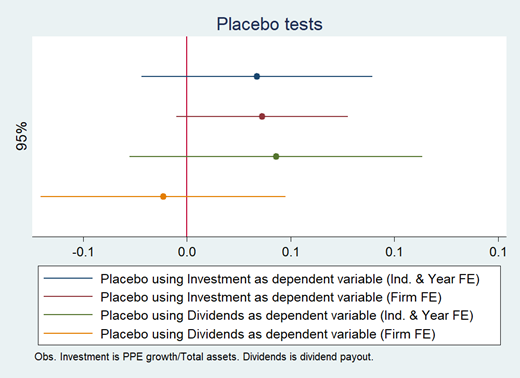

Two types of models:

Ind. Var.: Competition is the Herfindahl-Hirschman index

Brazil is not different than sample average

Model 1:

\(ESG_{i,t} = β_1 + β_2 × Competition_{i,t-1} + β_3 × Size_{i,t-1} + β_4 × MtB_{i,t-1} + \\ β_5 × Leverage_{i,t-1} + β_6 × Capex + RD_{i,t-1} + β_7 × ROA_{i,t-1} + \\ β_8 × Cash_{i,t-1} + ϕ_{time} + ϵ_{i,t}\)

Model 2:

\(ESG_{i,t} = β_1 + β_2 × Treated (Brazil) + β_3 × After (2015) + \\ β_4×Treated (Brazil) × After (2015) + β_5 × Size_{i,t-1} + β_6 × MtB_{i,t-1} + \\ β_7 × Leverage_{i,t-1} + β_8 × Capex + RD_{i,t-1} + β_9 × ROA_{i,t-1} + \\ β_{10} × Cash_{i,t-1} + ϕ_{time} + ϵ_{i,t}\)

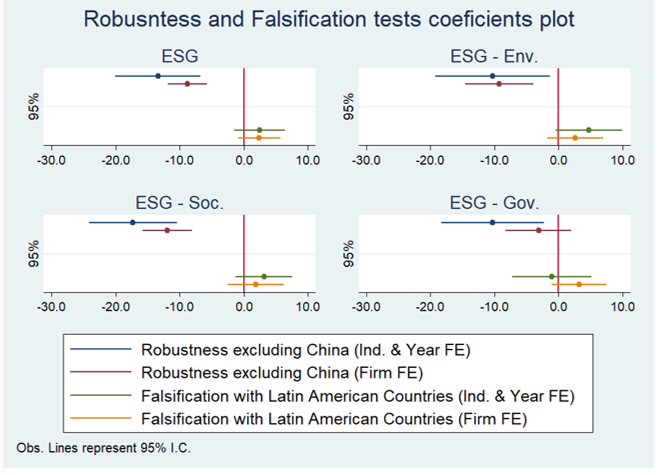

Robustness: Excluding China

Falsification: “Shock” in Latin America Countries, instead of Brazil

Which penalizes those assumed as less profitable in the short-term, such as ESG-related practices.

Results contradict US-based findings: Fernández-Kranz and Santaló (2010), Flammer (2015b), and Leong and Yang (2020).